A magazine where the digital world meets the real world.

On the web

- Home

- Browse by date

- Browse by topic

- Enter the maze

- Follow our blog

- Follow us on Twitter

- Resources for teachers

- Subscribe

In print

What is cs4fn?

- About us

- Contact us

- Partners

- Privacy and cookies

- Copyright and contributions

- Links to other fun sites

- Complete our questionnaire, give us feedback

Search:

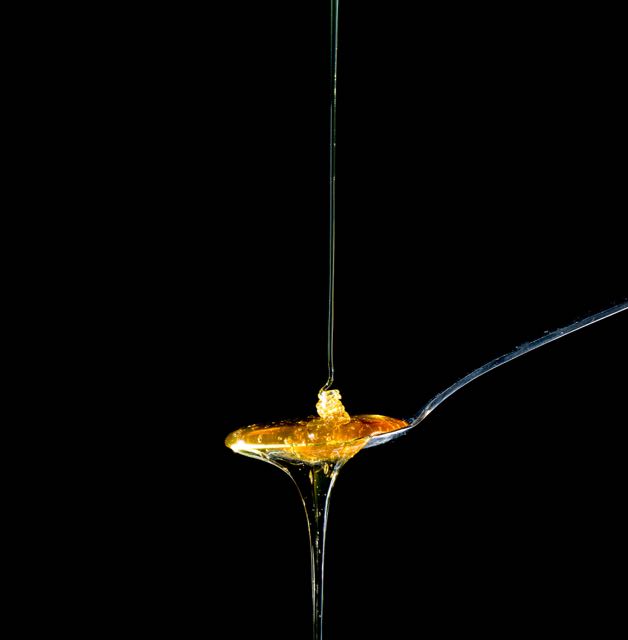

The Cyber-Security Honeypot

by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

based on a talk by Jeremiah Onaolapo, UCL

To catch criminals, whether old-fashioned ones or cybercriminals, you need to understand the criminal mind. You need to understand how they think and how they work. Jeremiah Onaolapo, a PhD student at UCL, has been creating cyber-honeypots and finding out how cybercriminals really operate.

Hackers share user ids and passwords they have stolen on both open and hidden websites. But what do the criminals who then access those accounts do once inside? If your webmail account has been compromised what will happen. Will you even know you've been hacked?

Looking after passwords is important. If someone hacks your account there is probably lots of information you wouldn't want criminals to find: information they could use whether other passwords, bank or shopping site details, personal images, information, links to cloud sites with yet more information about you ... By making use of the information they discover, they could cause havoc to your life. But what are cybercriminals most interested in? Do they use hacked accounts just to send spam of phish for more details? Do they search for bank details, launch attacks elsewhere, ... or something completely different we aren't aware of? How do you even start to study the behaviour of criminals without becoming one? Jeremiah knew how hard it is for researchers to study issues like this, so he created some tools to help that others can use too.

His system is based on the honeypot. Police and spies have used various forms of honeytraps, stings and baits successfully for a long time, and the idea is used in computing security too. The idea is that you set up a situation so attractive to people that they can't resist falling in to your trap. Jeremiah's involved a set of webmail accounts. His accounts aren't just normal accounts though. They are all fake, and have software built in that secretly records the activities of anyone accessing the account. They save any emails drafted or sent, details of the messages read, the locations the hackers come in from, and so on. The accounts look real, however. They are full of real messages, sent and received, but with all personal details, such as names and passwords or bank account details, fictionalised. New emails sent from them aren't actually delivered but just go in to a sinkhole server - where they are stored for further study. This means that no successful criminal activity can happen from the accounts. A lot can be learnt about any cybercriminals though!

Experiments

In an early experiment Jeremiah created 100 such accounts and then leaked their passwords and user ids in different ways: on hacker forums and web pages. Over 7 months hundreds of hackers fell into the trap, accessing the accounts from 29 countries. What emerged were four main kinds of behaviours, not necessarily distinct: the curious, the spammers the gold diggers and the hijackers. The curious seemed to just be intrigued to be in someone else's account, but didn't obviously do anything bad once there. Spammers just used the account to send vast amounts of spam email. Gold diggers went looking for more information like bank accounts or other account details. They were after personal information they could make money from, and also tried to use each account as a stepping stone to others. Finally hijackers took over accounts, changing the passwords so the owner couldn't get in themselves.

The accounts were used for all sorts of purposes including attempts to use them to buy credit card details and in one extreme case to attempt to blackmail someone else.

Similar behaviours were seen in a second experiment where the account details were only released on hidden websites used by hackers to share account details. In only a month this set of accounts were accessed over a thousand times from more than 50 countries. As might be expected these people were more sophisticated in what they did. More were careful to ensure they cleared up any evidence they had been there (not realising everything was separately being recorded). They wanted to be able to keep using the accounts for as long as possible, so tried to make sure noone knew the account was compromised. They also seemed to be better at covering the tracks of where they actually were.

The Good Samaritan

Not everyone seemed to be there to do bad things though. One person stood out. They seemed to be entering the accounts to warn people - sending messages from inside the account to everyone in the contact list telling them that the account had been hacked. That would presumably also mean those contacted people would alert the real account owner. There are still good samaritans!

Take care

One thing this shows is how important it is to look after your account details: ensure no one knows or can guess them. Don't enter details in a web page unless you are really sure you are in a secure place both physically and virtually and never tell them to anyone else. Also change your passwords regularly so if they are compromised without you realising, they quickly become useless.

Of course, if you are a cybercriminal, you had better beware as that tempting account might just be a honeypot and you might just be the rat in the maze.