A magazine where the digital world meets the real world.

On the web

- Home

- Browse by date

- Browse by topic

- Enter the maze

- Follow our blog

- Follow us on Twitter

- Resources for teachers

- Subscribe

In print

What is cs4fn?

- About us

- Contact us

- Partners

- Privacy and cookies

- Copyright and contributions

- Links to other fun sites

- Complete our questionnaire, give us feedback

Search:

A brief history of the digital revolution, part 1: from birth to the moon

The Royal Institution Christmas Lectures 2008 invited you on a high tech trek to build the ultimate computer. If you missed these fascinating lectures on channel Five you can still order the DVD and join Prof Chris Bishop on his exploration of the exciting world of computer science. The Christmas Lectures talk a lot about the current cutting-edge of computer technology, but what were things like in the early days of the digital revolution? The researcher for the 2008 Christmas Lectures, Lewis Dartnell, takes us through the story.

Electronic computers have come a long way since their birth only 50 years ago. One of the very first digital computers was built at the University of Manchester, a prototype called Manchester Mark I. The machine was revolutionary, with its complex processing circuits and storage memory to hold both the program being run and the data it was working on. The Mark I was first run on 21 June 1948 and paved the way as a universal computer that is truly versatile and can be reprogrammed at will, rather than being hard-wired for a single particular task.

These earliest computers used technology called vacuum tubes, which were essentially just like filament light bulbs. Because they get so hot, such vacuum tubes were really power hungry and not very reliable. Typically, computers like the Manchester Mark I, processing using vacuum tubes, could only be run for a few hours at a time before one of the vacuum tubes broke and had to be replaced. The biggest break-through in modern computing came with the invention of the transistor, a small electronic component that can perform the same function as a vacuum tube, but is much more energy efficient and reliable. The beauty of the transistor is that computer scientists found ways of making them smaller and smaller, and to connect a number of them together into a single miniaturized processing board called an integrated circuit. These came to be knows as microchips, and form the basis of all the computers made today.

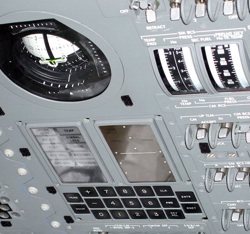

A major drive for the development of microchip technology was the Apollo programme, begun in 1961 to land humans on the Moon. Although the vast majority of the complex calculations to do with plotting the trajectory and navigating to the moon were performed by enormous banks of computers back on Earth, it was crucial for the spacecraft to have their own on-board computer system. This was called the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), and both the command module and the lunar module, which actually made the descent to the surface of the moon, had one each. These ground-breaking computers provided the astronauts with crucial flight information, helped them make course corrections and to touch-down gently on the moon’s surface. Because it’s absolutely crucial to reduce the amount of mass and power usage on a spacecraft as far as possible, developing these guidance computers really pushed the technology in miniaturising integrated circuits.

The Apollo Guidance Computer not only helped drive the early development of microchips, but it also suffered one of the most infamous computer crashes in history. During the descent down to the Moon’s surface the AGC started displaying two error messages that the two astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, weren’t familiar with. Engineers back at mission control on Earth quickly tried to identify the error code, and what it might mean for the lunar landing. Something that had never happened in any of the training simulations was now overloading the flow of data into the computer, the first time it had ever been used for real. Time was running out with only a limited amount of rocket fuel on-board and the Moon rushing up towards them. Luckily the computer entered a fail-safe mode, aborting low-priority calculations but able to continue with the critical tasks for the landing.

It wasn’t until the investigation afterwards that it was realized just how lucky Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had really been. The root of the problem was that the real attempt at the Moon landing was the first time an important radar system had been plugged into the computer, sending data into the AGC that wasn’t needed for the landing. This almost totally overloaded the computer, but by amazing luck, the amount of spare processing power built into the system for safety was almost exactly the amount being wasted by the un-needed radar, and the AGC didn’t crash completely.

The story of the digital revolution continues in part 2.

To find out more about computers, watch the 2008 Royal Institution Christmas Lectures and join Prof Chris Bishop on his high-tech trek to build the ultimate computer. You can order a DVD of these lectures from the Christmas Lectures website. This website is an exciting extension to the Christmas Lectures, with five zones to explore and lots of fun games to play. Take the challenge to design your own fastest microprocessor chip or try to work out how the processing power of objects like mobile phones and MP3 players compare against each other.

The author, Lewis Dartnell, worked as researcher for the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures. You can read more of his writing at lewisdartnell.com.